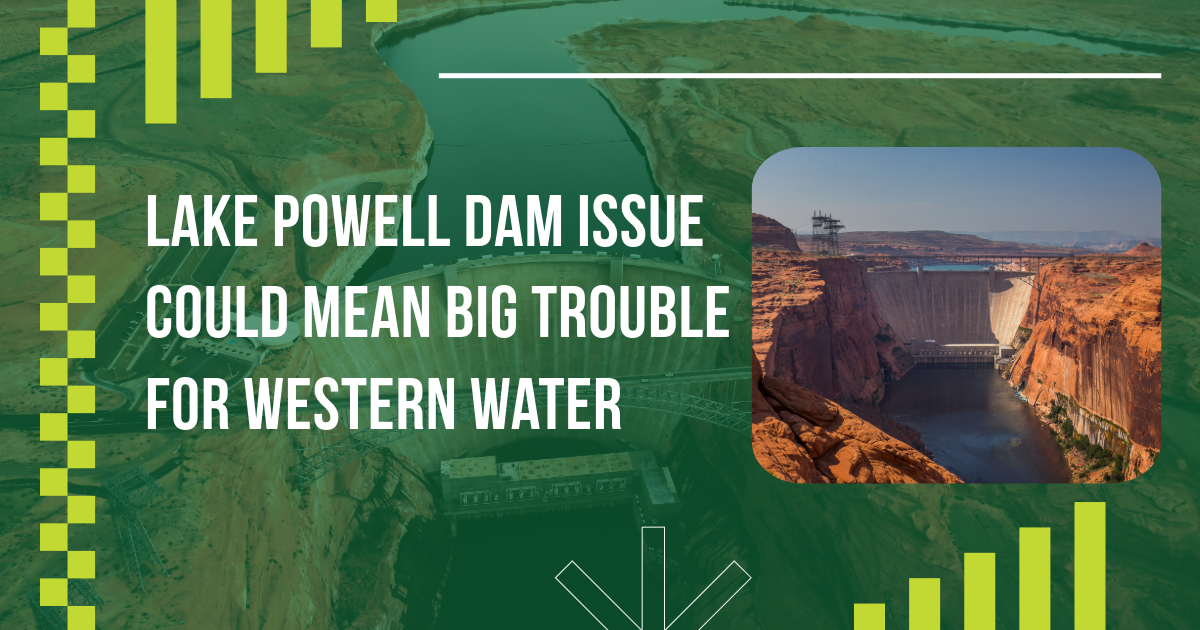

The Glen Canyon Dam holds back Lake Powell. As the lake’s level has plummeted to historic lows, some concerns that wear on dam’s infrastructure, originally designed to manage high water levels, could significantly disrupt the flow of the Colorado River.

Conservation groups are urgently calling for changes to the management of Lake Powell, the nation’s second largest reservoir, following the alarming discovery of damaged plumbing within the dam that contains it.

The damage affects Glen Canyon Dam’s “river outlet works,” a crucial set of small tubes located near the bottom of the dam. These tubes were originally designed to release excess water when the reservoir was nearing full capacity.

The reservoir is currently only 32% full, severely impacted by climate change and constant demand. Water experts fear that the river outlet works may soon become the sole method to transfer water from Lake Powell, located in far northern Arizona, to the Colorado River. However, they are concerned that damage to these tubes could hinder the ability to use them regularly.

This is the latest development in the ongoing saga of Glen Canyon Dam, which has already been a focal point of concern about the shrinking Colorado River, even before the damaged pipes were discovered. Water experts fear that Lake Powell could drop so low that water would be unable to pass through the hydropower turbines, which generate electricity for about 5 million people across seven states. If the water levels drop, it could prevent any water from passing through the dam at all, keeping it out of the Grand Canyon just downstream of Lake Powell.

The threat of that reality has led advocacy groups to ring the alarm.

“This situation poses a significant threat to our water delivery system,” stated Eric Balken, executive director of the Glen Canyon Institute. “This is a significant infrastructure issue, that impacts water is management across the entire basin.”

The recent damage to the outlet works is the result of a process known as “cavitation.” It happens when tiny air bubbles in the water burst while moving through the dam’s plumbing. That implosion is enough to generate shock waves that tear away small chunks of protective coating insides the pipes.

In recent years, the outlet works have been used to release temporary bursts of water designed to enhance ecosystems in the Grand Canyon. The cavitation damage was discovered during pipe inspections following a series of these planned water bursts in April 2023.

In an informational webinar last month, Reclamation officials explained that the damage was not due to a single event, but had developed gradually over time.

Nick Williams, Upper Colorado River power manager for the Bureau of Reclamation, stated that cavitation damage becomes more likely when reservoir levels are low.

The river outlet works can still carry water, but will require repairs, such as a fresh coating of epoxy which is scheduled for either later this year or early 2025.

Legal risk and threats to fish.

Even with a fully operational river outlet works system, these pipes can handle only a limited amount of water. If the outlet works become the sole method for passing water through the dam, Upper Basin states of the Colorado River’s, Colorado, Wyoming, New Mexico, and Utah – could fail to meet a longstanding legal obligation to deliver a specified amount of water to their downstream neighbors each year.

The Colorado River Compact, a 1922 legal agreement that forms the modern foundation of water management in the arid West, requires the Upper Basin to pass 7.5 million acre-feet of water annually to the Lower Basin states of California, Arizona and Nevada each year.

An acre-foot is the amount of water required to cover one acre of land to a depth of one foot. One acre-foot typically supplies enough water for one to two households for an entire year.

Lake Powell is frequently described as the Colorado River’s “savings account,” where the Upper Basin states store water to make sure they always have enough to meet up with their legal obligation to direct water downstream. The Lower Basin stores these water deliveries in Lake Mead, its “checking account.” Lake Mead, the nation’s biggest reservoir, holds water that flows to cities such as Las Vegas, Phoenix and Los Angeles, and to extensive agricultural fields in California and Arizona.

Conservation groups have previously cited the limited capacity of the outlet works in their calls for a change in the way Lake Powell’s management. They warn that the recent damage could make the outlet works unusable, only worsening the challenge of maintaining downstream water flow from Lake Powell.

“If you lose your job, you don’t go out and buy yourself an elaborate dinner, justifying it by saying, ‘I still have money in my checking account,” said Zach Frankel, executive director of the Utah Rivers Council. “You go, ‘Wow, I lost my income. I need to review my expense budget and tighten my belt? The Colorado River Basin has yet to adopt this mindset”

In recent years, Lake Powell has barely maintained a high enough level for water to pass through the hydropower turbines. That’s the result of a shell game by water managers, who have shuffled water from upstream reservoirs Lake Powell on an emergency basis.

Damage to the outlet works also raises concern about invasive fish entering the Colorado River section that flows through the Grand Canyon. Dropping water levels have enabled invasive smallmouth bass to swim through to the other side, where they can eat native humpback chub, a species protected by the Endangered Species Act.

Recently, federal water managers unveiled plans to protect the at-risk humpback chubs. Those plans moderately rely on the capacity to release cold water across the river outlet that works into the Grand Canyon. Wildlife advocates had already criticized those plans even before the news of damage to the river outlet works, which could further undermine native fish conservation efforts.

Future Solution and Fixes.

The seven states that rely on the Colorado River are currently caught in a deadlock over how to cut back on water demand. They are negotiating a new set of rules for sharing the river, intended to replace the current guidelines expiring in 2026, but they are stuck in an ideological impasse.

The new set of rules could theoretically establish a long-term plan for managing the West’s major reservoirs sustainably, allowing water managers to move on beyond the patchwork of emergency measures that have only temporarily mitigated issues at Glen Canyon Dam.

Balken, from the nonprofit Glen Canyon Institute, stated that policymakers should contemplate major changes to the dam’s operation.

“If we aim to recondition this river structure to be climate resilient and upgrade our infrastructure to cope with impacts of climate change, we must seriously consider bypassing Glen Canyon Dam,” Balken said.

In March, Upper Basin and Lower Basin states released competing plans for post- 2026 river management. Subsequently, a coalition of environmental nonprofits released their own plan, a group of tribes that rely on the Colorado River has issued a set of principles they hope will be incorporated into future water management.

The Biden administration is urging states to reach a compromise before the end of 2024, aiming to avoid complications that could be brought on by a change in presidential administration after the November election.